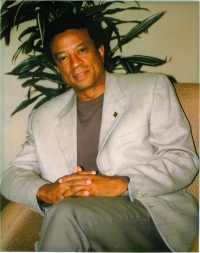

R. Chapman Wesley

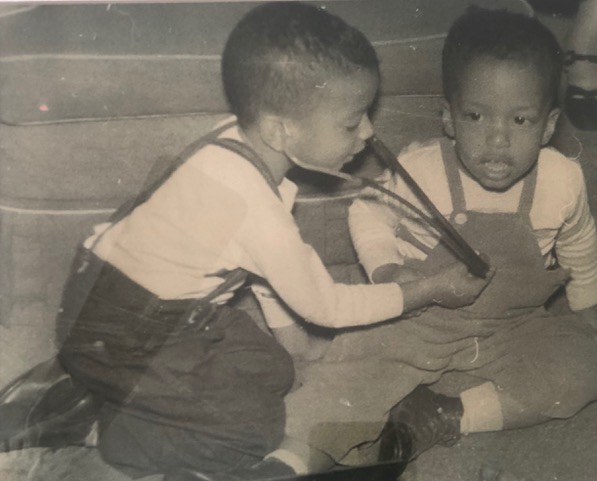

I grew up in rural central Virginia the namesake of my African American family physician father, Dr. Robert C. Wesley, and my educator mother, Anne Louise Reynolds, destined to be a physician as evidenced by the photo of me at age 4 with my brother Ron.

I grew up in rural central Virginia the namesake of my African American family physician father, Dr. Robert C. Wesley, and my educator mother, Anne Louise Reynolds, destined to be a physician as evidenced by the photo of me at age 4 with my brother Ron.

Now, in the twilight of my medical career, I have devoted myself to writing and my ongoing exploration of the esoteric underpinnings of Life, beginning with but not exclusively of the tenets of Taoism.

King Wen channeling Lao Tzu: "The town may change. But The Well cannot be changed. All draw from The Well. But if the rope is short, or the jug breaks, MISFORTUNE!

According to Lao Tzu, The Well, an image of nature combining the qualities of water and wood, is an inexhaustible source of nourishment to all. From this mystical source, always available, success in any aspect of one's life is dependent upon withdrawing a sufficient amount. We can take as much as we can and desire, for it is freely given. A necessary step is simply the recognition that it is always there, always available.

The outpourings that have filled my Well arise from many sources, some known and some very unknown. Childhood exposures to oceans, lakes, and rivers have played definite roles.

From college days to this day, The I Ching commentary, propagated by seeming random probability but somehow based on an subconscious synchronicity, has informed the intuitive side of my life. Randomly juxtaposing states of nature, The I Ching reveals 64 conditions defining the relationship of individuals to each other, to nature, to society/government, to the Divine, and the Divine to everything. My inquiry has been amplified by the poetry of the Tao Te Ching and the concept of an inscrutable Tao, or The Way, from which everything emerges.

Fascination with numbers has had a profound effect upon me. Numbers seem to govern the entire universe. The patterns in numbers, like the Fibonacci Sequence, are deducible from ever-accumulating observations and provide ever-increasing insight and clarity to our approximations of the universe and reality itself.

We may never truly know what; but we can increasingly know how.

My career-long study of clinical hypnosis has also been profoundly important. I cannot do justice to this subject except to say that hypnosis is one of the most important and cost-effective tools in clinical medicine that is currently not being widely applied.

I would be truly remiss not to mention the work of Ernest Holmes and his seminal work, "The Science of the Mind", which I have studied daily in some form for over 25 years.

The reading of James Redfield's “The Celestine Prophecy” has been an overpowering influence, in which he recounts how synchronous, seemingly random occurrences and anomalies can play a vital role in our journey of self-discovery.

Fascination with art in all its forms and the study of African Art with my undergraduate mentor and friend, Prof. Robert F. Thompson of Yale, shaped me during those formative years.

I love the deeply spiritual, modern works and paintings of Abdul Mati Klarwein and hope that you might seek them out.

I have been deeply influenced by the Avant-garde, non-commercial Jazz of the 60s, 70s, and beyond. I truly hope to be a part of re-introducing its vitality to the World.

During residency, I had exposure to immunology, virology, infectious diseases, and oncology, subjects explored in The Well, none of which underpin my scope of practice (cardiology).

My lifelong concern over global health threats, originally regarding the threat of nuclear weapons, propelled me to investigate pandemic threats since the initial bird flu scares of the early 2000s.

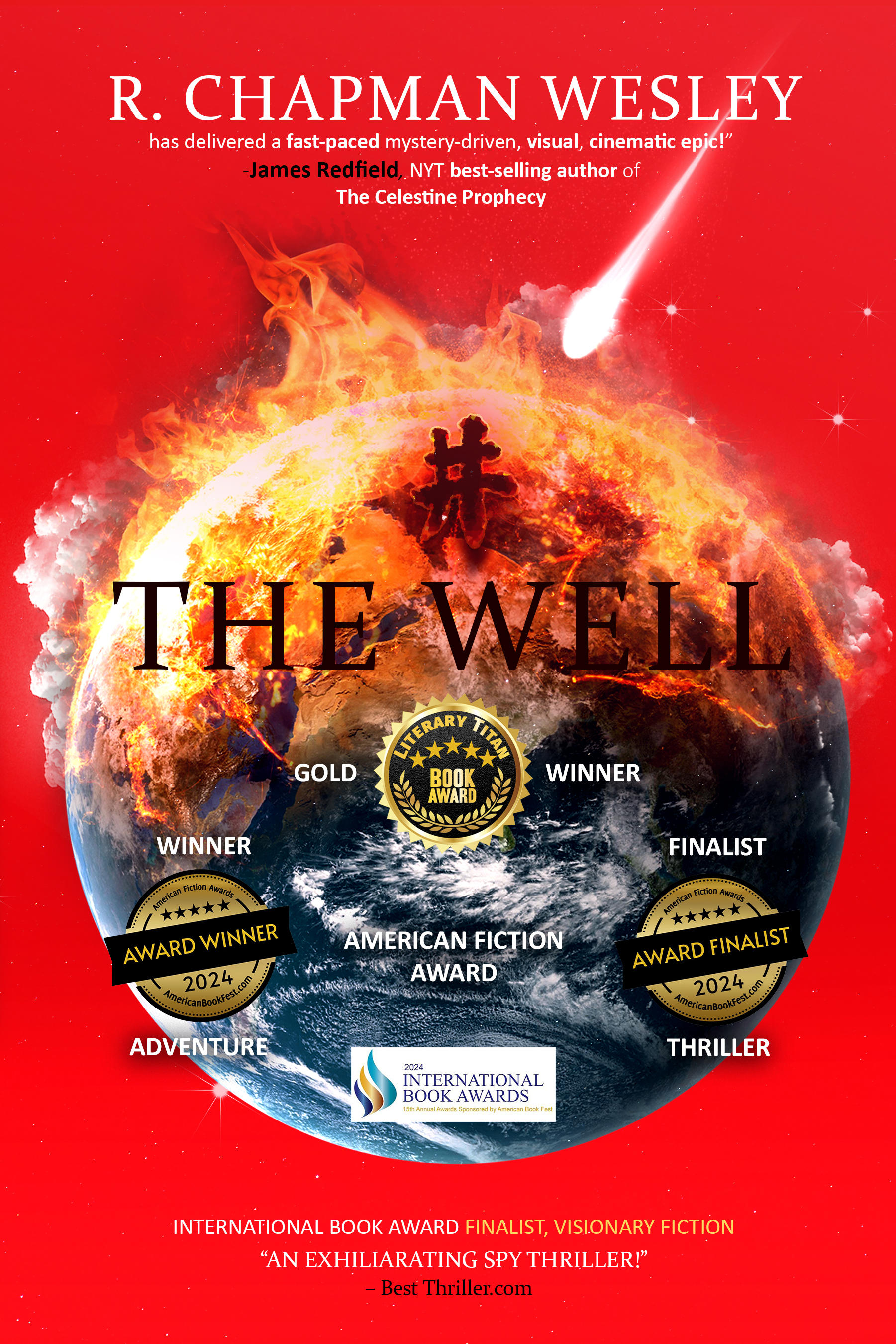

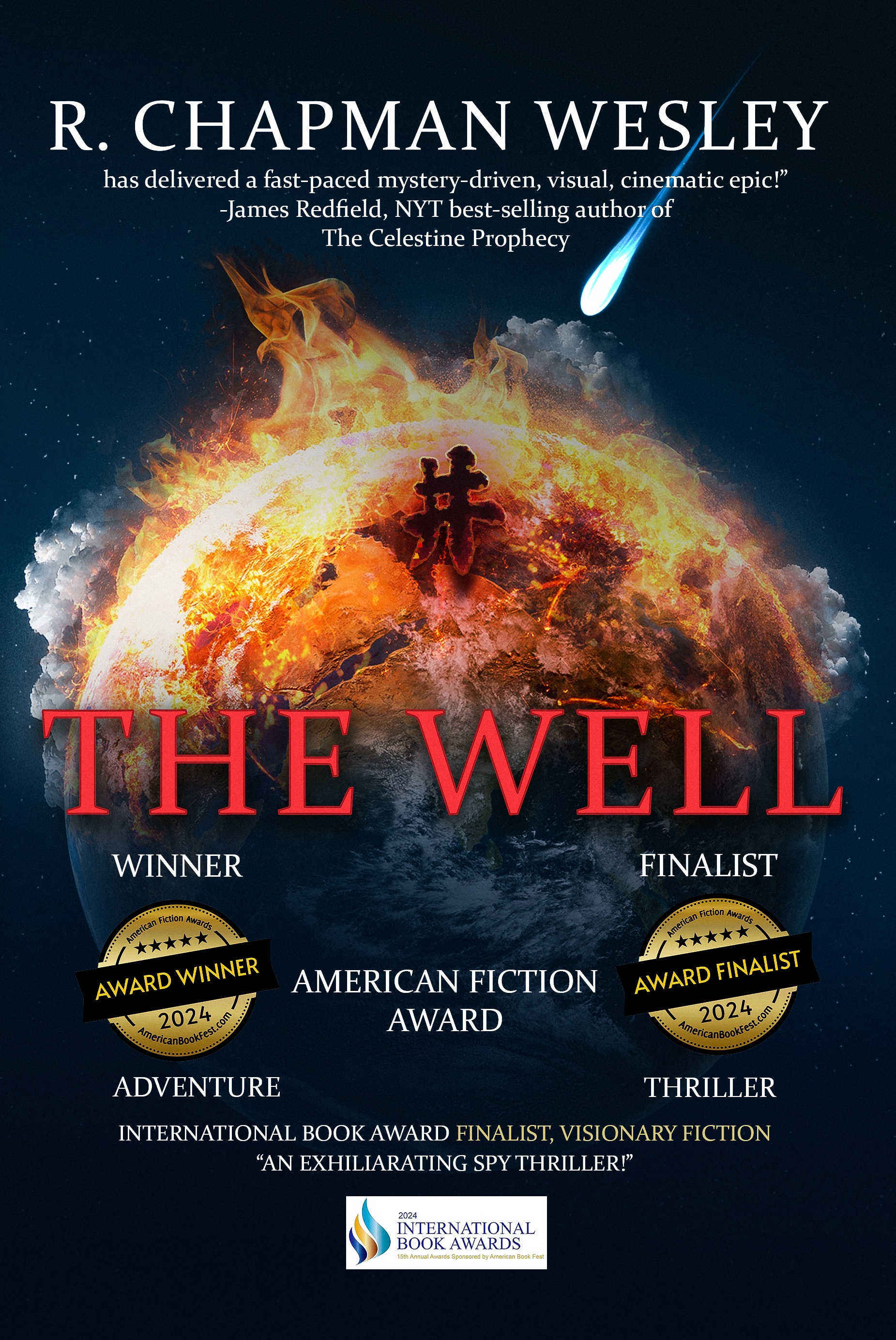

Having said all that, the imaginings of this book should not be viewed as science. I totally made the whole thing up, well in advance of the Coronavirus Pandemic. My initial inklings came in Thailand in the spring of 2018, followed by a story outline composed in Shanghai Airport on my return flight to the U.S. That led to drafting of a screenplay over several years. After many drafts, the story congealed into a novel and an unabridged audio book.

Hopefully you find "The Well" entertaining and lending some measure of insight into the human condition. That is all an artist, and hopefully any scientist, can hope for.

R. Chapman Wesley, Recipient of the 2025 Literary Titan Book Award

Shepherd.com invited R. Chapman Wesley to share "The best books about suspenseful spiritual transformation." Click here to read the article.

IndieView interviewed the author about The Well.

Dr. Wesley and Tania Reis Zakhariants perform a salsa at "From the Heart Group" fundraiser.

Dr. Wesley and Tania Reis Zakhariants perform a "Funky Cha Cha."